Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, causes and antibiotics

SBP is a life-threatening infection of ascites in the absence of an intraabdominal source of infection. Secondary infection of ascites is likely to be associated with abdominal paracentesis, colonic perforation or dilatation, or any intra-abdominal source of infection. SBP develops in about 8% of cirrhotic patients with ascites, particularly with severe liver dysfunction (Child-Pugh class B or C).

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- The highest risk of SBP is those with:

- Acute GI bleeding,

- Low total protein concentration in ascitic fluid.

- Previous SBP episode.

- Using of PPI.

Pathogenesis

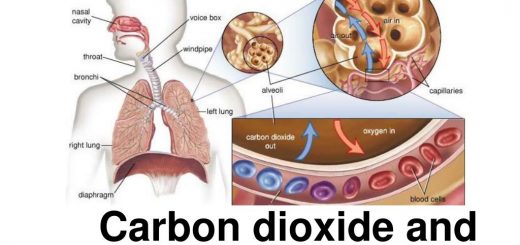

The pathogenesis of SBP includes both a pathological bacterial translocation from the gut to the systemic circulation and then to the ascitic fluid due to a disruption of the intestinal permeability and motility and an impaired ability of the local and systemic immunity to control the spread of bacteria.

The most frequently cultured organisms in the ascitic fluid of patients with SBP are Gram-negative bacteria: Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Less commonly, Gram-positive bacteria; Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., and Enterococci are isolated.

Clinical picture

Manifestations of SBP may not be impressive and may misguide the physician. Deterioration of hepatic function and hepatic encephalopathy. Renal complications with azotemia. Patients with SBP may be asymptomatic or complain only of mild vague symptoms:

- Pyrexia.

- Local abdominal pain.

- Abdominal tenderness.

- Diarrhea.

Diagnosis

SBP should be suspected if a patient with known cirrhosis and ascites deteriorates, particularly with hepatic encephalopathy or azotemia. Diagnostic paracentesis should be done in all patients with cirrhosis and ascites particularly:

- On hospital admission (regardless of whether they exhibit clinical symptom(s) of SBP).

- Who deteriorate clinically (e.g. encephalopathy, azotemia, fever) without an obvious cause.

- Gl bleeding.

SBP is diagnosed by an elevated absolute polymorphonuclear leukocyte count (PMN) ≥ 250 cells/mm³ in the ascitic fluid with or without a positive ascitic fluid culture (usually monomicrobial and mainly Gram-negative).

Ascitic fluid protein is 1 g/dl. Patients who have negative cultures, are diagnosed as “culture-negative neutrocytic ascites”. (also Consider TB peritonitis, peritoneal carcinomatosis, and spontaneous fungal peritonitis). In some instances, patients may have monomicrobial, non-neutrocytic ascites described as “bacterascites”.

Ascitic fluid analysis

- An ascites-specific dipstick for detecting a neutrophil count ≥ 250 cells/mm³, has 100% sensitivity.

- Ascitic fluid leukocyte esterase dipstick for detection of an elevated ascitic fluid PMN count.

- In Situ Hybridization method for detecting bacterial DNA phagocytized in neutrophils and macrophages in ascitic fluid (more sensitive, one day vs. blood culture).

SBP vs. Secondary peritonitis

likely to be associated with abdominal paracentesis, colonic perforation or dilatation, or any intra-abdominal source of infection.

2ry bacterial peritonitis should be suspected if:

- Total protein concentration > 1-1.5 g/dL.

- PMN in ascites is > 5,000 neutrophils/mm³.

- Polymicrobial in ascites culture.

- A failure of neutrophil count to fall after 48h of antibiotic therapy.

Other characteristics of 2ry bacterial peritonitis:

- Ascitic fluid glucose concentration < 50 mg/l.

- Ascitic LDH concentration > serum LDH levels,

- Ascitic alkaline phosphatase > 240 U.

Prognosis of SBP

Without adequate prophylaxis, 30-50% of patients with SBP will die during that hospital admission, and 69% will recur in 1 year, and again 50% will die. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment have reduced early mortality from approximately 80% to 15-20%.

Predictors of mortality in SBP include:

- Severe underlying liver disease.

- Renal impairment.

- The onset of severe sepsis.

- Recent gastrointestinal bleeding.

Prophylaxis of SBP

Prophylaxis of SBP with norfloxacin 400 mg twice daily.or ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is recommended in these conditions:

- After episodes of GI bleeding.

- Previous episode of SBP.

Long-term antibiotic administration in patients with total protein concentration in ascitic fluid below 1.5 g/dl is not settled due to the emergence of multi-drug-resistant bacteria.

Treatment of SBP

- Empirical antibiotic therapy should be started immediately with suspicion of SBP.

- 3rd generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone or cefotaxime 2g intravenously every 12 h or every 8 h for a minimum period of 5 days are often the treatment of choice.

- Alternatively, the combination of beta-lactams plus beta-lactamases inhibitors (amoxycillin-clavulanic acid) or beta-lactams plus fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin ofloxacin) has similar efficacy.

- When culture results are available, antibiotic treatment is revised to minimize the risk of further antibiotic resistance.

- when the ascites PMN count decreases to < 25% of the pretreatment value after 2 d of antibiotic treatment, then there is an increased probability of failure to respond to any treatment.

- In hospital-acquired infections, multi-drug resistant pathogens are more often cultivated, which in turn contributes to less effective treatment and worse prognosis.

- Patients with SBP and signs of hepatic dysfunction or signs of renal impairment should further be given albumin infusion.

Spontaneous fungal peritonitis (SFP)

- SFP is a less common complication (Of spontaneous peritonitis cases, 0%-7.2% are culture positive for fungus) of advanced cirrhosis in the absence of other causes of intra-abdominal infection.

- A PMN count of ≥ 250 cells/mm³ or more in the ascitic fluid with a positive fungal culture regardless of bacteria is diagnostic of SFP.

- Fungal translocation may be facilitated by upper gastrointestinal bleeding, Immunosuppression and malnutrition.

- Direct percutaneous inoculation of fungi is the proposed route of fungal infection in patients with refractory ascites and a history of paracentesis.

Causative fungi include:

- Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei.

- Cryptococcus spp.

- Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp.

Treatment of SFP

- The mortality is high because of delayed diagnosis, lack of clinical signs, lack of suspicion of SFP, and delay in the treatment with antifungal therapy.

- Echinocandins are recommended as first-line treatment for patients with cirrhosis and nosocomial SFP or critically ill patients with cirrhosis and community-acquired SFP.

- Fluconazole is recommended for less severe infections.

- However, directed antifungal therapy may not improve the outcomes of some patients with SFP because of a lack of response to the administration of empirical treatment and delay in starting antifungal therapy.

You can subscribe to science online on Youtube from this link: Science Online

You can download Science Online application on Google Play from this link: Science Online Apps on Google Play

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) risk factors, diagnosis, symptoms, types, causes and treatment

Refractory ascites symptoms, cause, types and treatment of refractory ascites in cirrhosis

Ascites cause, grades, symptoms, diagnosis and Treatment of cirrhotic ascites

Liver Cirrhosis causes, symptoms, treatment & stages, Liver Biopsy and treatment of PHTN

Viral hepatitis, HDV symptoms, Treatment of acute HCV, Occult hepatitis C and HEV

Acute Hepatitis Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Chronic hepatitis and Liver biopsy

Liver development, congenital anomalies, function & Pancreas development